ENCAPSULATION SUITS

Artefacts can sometimes grow beyond their intended function. Some objects can even demand from their user a different set of rules in order to handle them. In some way or another, they take on a form of life within the mind, cause inconvenience, and change behaviour. But they are still essential to daily life. How and why do certain domestic objects become so powerful?

“Forget that commodities are good for eating, clothing and shelter; forget their usefulness and try instead the idea that commodities are good for thinking; treat them as a nonverbal medium for the human creative faculty.”—Mary Douglas and Baron Isherwood

Yuka Oyama was originally trained in the field of Contemporary Jewellery Art, and as a result, her art practice stems from the inseparable and intermediary relations between a person and an object. Encapsulation Suits is the core work of her PhD in artistic research, which she conducted at the Art and Craft of Oslo National Academy of the Arts, funded by the Norwegian Artistic Fellowship Programme, from 2012 until 2017. During this time, she investigated how a person and an object can activate each other both physically and psychologically. Specifically, she researched how the active, fluid, and dynamic inner life of objects that we project onto them during daily life can be expressed through worn sculptures that are set in motion.

In The System of Objects, Jean Baudrillard discusses two different types of objects: The first type is a commodity, such as a refrigerator, serving a practical function. The second type is an object that enters into subjective relationships with the owner, and in this sense no longer serves as a commodity. It gains persona and thus people wish to possess it.[1]

In 2013, Oyama asked herself, of everything she owns, what are the five most special objects that she is emotionally attached to? She chose a bag of flour, a bundle of keys, a headdress, a handbag, and a piano. She aimed to find out what kind of inner forces are inherent to these objects that made them appear powerful to her. Then, she constructed life-sized wearable objects so that she could enter into physical dialogues with her emotionally evocative objects through wearing, enacting, and becoming them.

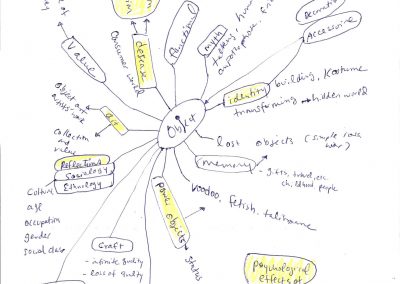

RESEARCH PROCESSES AND METHODS

STAGE 01 FIELDWORK, PUBLIC INTERVENTIONS AND WORKSHOPS

Oyama seeks to investigate the imagined life inherent in objects that we own. She began this research phase by deploying interventions and workshops in the public space and asking random people to draw their “most-special-object” in an imagined anthropomorphized life state. She then translated people’s object stories into small figures made out of textile and clay. By going through this process, she learned that these figures needed to be made in human-size—not cute—in order to express autonomy of the objects.

STAGE 02 CONSTRUCTIONS OF WEARABLE SCULPTURES

She then made a rough draft of four sculptures, a wardrobe, a fire alarm, a drill, and a bag of flour out of polyethylene sheets using black hot glue. Three of them stemmed from someone else’s object stories, while one was the artist’s.

STAGE 03 TWO PERFORMANCES

Next, she examined how to perform the wearable sculptures out on the street and in her studio. In both attempts, she was not convinced that the enactment of sculptures conveyed the agentive quality of the objects. She then decided to focus only on her own object stories. She resumed making the five sculptures: Headdress, Piano, Key, Bag of Flour, and Handbag.

STAGE 04 FIRST CHOREOGRAPHIC EXPERIMENTS WITH A MIME DANCER

Together with a mime dancer, Oyama examined particular characteristics, genders, and possible movements for each sculpture based on mime techniques. Oyama felt that the performances created felt artificial.

STAGE 05 SECOND CHOREOGRAPHIC EXPERIMENTS ON MY OWN

She reiterated the main objective of this research once again, asking herself, “Why are these objects so powerful to me?” She then realised that she needed to enter into even deeper physical dialogues with each object sculpture and she should perform herself. She set up a video camera and examined movements, where she and her sculpture would merge. She filmed five performances that she performed.

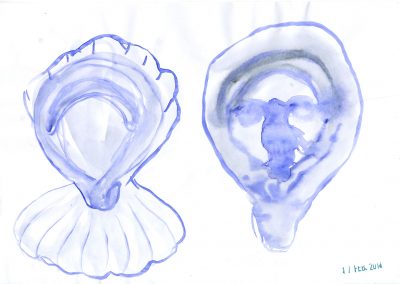

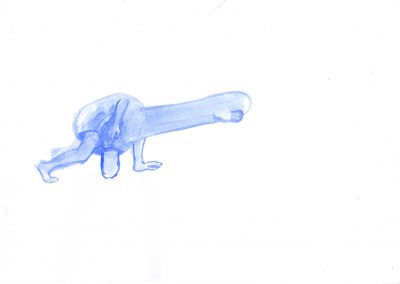

OUTCOME

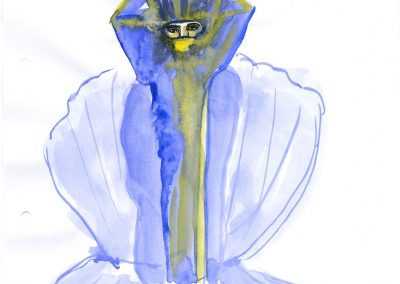

Encapsulation Suits was developed from 2012 to 2017. Oyama says of the process, “it felt like chasing a ghost, something that was compelling and incomprehensible. I often felt stuck, so I took many breaks and worked on other artworks such as Collectors, Cleaning Samurai, Helmet – River, Modern Ballet, and Weavers.” Ironically, these artworks depicted objectification and mechanisation of people, exactly the opposite of her research objective: ‘the life of objects.’ She originally planned to work in collaboration with dancers in order to develop the performance. However, towards 2014/2015, she decided to focus on her own object relations in even more depth. She then worked extensively on creative writing and sketching in watercolour. On her own, she also studied physical constraints given by the weights and forms of the worn sculptural objects. She observed movements where she and her sculpture and would appear as one entity.

The artist discovered that, “it was curious and fascinating to see how some of the sculptures demanded slow movements, whereas others abrupt and rough motions. Gradually, I recognised that it was my personal relationships to specific people, memories and issues that mattered to me in my object-and-I hybrid creatures. Eventually, the emotionally loaded objects that I owned taught me much about who I am as a person, how I want to be as a woman, an artist, and a mother. The whole process almost resembled a self-made psychoanalysis.”

Hans Peter Hahn, a German anthropologist, claims that people remember what has happened in their life by pairing up events with objects, because objects are the co-actors of our everyday life. Furthermore, objects do more than just remind people of something or someone. They also absorb feelings and awareness that we do not consciously recognise. Objects can contain the side effects of past events and a “surplus of perceptions,” which Hahn explains, can evoke the unconscious and give surprising perspectives on personal experiences, making the owners of them look at daily life differently. Therefore, Hahn states that objects may appear to have a life of their own, allowing or restricting people’s intended actions in daily life, and communicating desires and feelings. This makes objects appear as if they were stubborn: they have agency and act on people.[2]

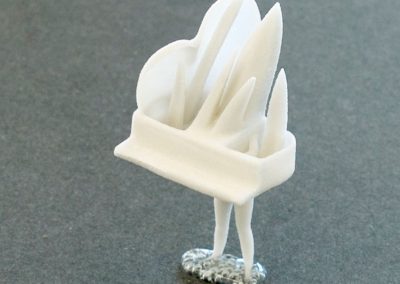

As the result of her research process, Oyama explains that “after going through this enormous journey with my objects, I wanted to reward myself with a medal. I then made a pendant Piano-and-I. I scanned the Piano sculpture and my body, and transformed them in silver, 5 cm in height. In this piece, I finally discovered my approach to jewellery that I had always been searching for: Jewellery that is beyond design and material value. Piano-and-I embodies strong emotional ties to myself and my past, a reminder of who I am, where I am from, and who I want to be. It also symbolises a new beginning of many possibilities ahead and it will accompany me in my future journey.”

—–

[1] Jean Baudrillard, The System of Objects (London, New York: Verso, 1996), PP. 91 – 92.

[2] Hans-Peter Hahn, ed., Vom Eigensinn der Dinge (Berlin: Neofelis Verlag, 2015), p.11.

OBJECT STORY ARCHIVE 01 Headdress

“In my family, wearing a hat always symbolises the western culture. I always hide myself in hats. The bowing gestures of this sculpture resembled Japanese politeness and being reserved. It seemed as if I was building walls around me and turning into an object.”

OBJECT STORY ARCHIVE 02 Piano

“Piano represents my mother who is a pianist. You have to go to the piano to play; piano does not come to play with you. She has always followed her passion and played a central role in her community as an artist. I am always proud of her, but when I was little I wished that she could be there for me more. After becoming a mother myself, I learned it was tough to be a mum like she was, not sacrificing her passions in order to cater to others’ needs. Piano resonates my process of redefining my view of an ideal woman.”

(Image source: http//:colibri-pianos.de/images/Instrunments/Steinway/C/Steinway_C_227_bw.jpg)

OBJECT STORY ARCHIVE 03 Handbag

“When a handbag goes missing, it is an indication that my mind is out of balance. I fear these moments. During the experiment with gestures, I was carrying Handbag on my back, which slid off me like a snail. Despite the struggle to crawl across the floor, the external appearance of the Handbag was graceful. It was telling me to slow down and go at my own pace.

Just before filming Encapsulation Suits, I forgot my handbag on a train. A man contacted me through email. I met him on a platform of a station. I learned that handbags could return.”

OBJECT STORY ARCHIVE 04 Key

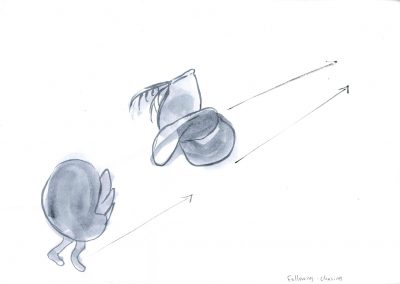

“We only give keys to adults that keep our secrets—it is a sign of trust. During the choreography test, Key started running against a door. It looked like a battering ram that knocks down a gate at the beginning of a revolution. Key told me to start a revolution and move on.”

OBJECT STORY ARCHIVE 05 Bag of flour

“In 2013, I was scared of flour products like cookies, bread, noodles, but I could not help not eating them. It gave me a different body, and it felt like living in someone else’s body. Bag of Flour tempts a woman, absorbs her from inside, sucks her soul, and kills her. But she reawakens and becomes a stronger house.”

-Yuka Oyama

Encapsulation Suits, 2017

A two-channel video, 4K, sound, five sculptures, a pendant.

EXHIBITION:

OSLO KUNSTFORENING, OSLO

Installation, 2015

Photograph: Christina Leithe Hansen

AKADEMIROMMET AT KUNSTNERNESHUS, OSLO

Installation, 2017

A two-channel video, 4K, sound, three sculptures, a pendant, and a live performance.

Whole cycle of works takes 25 minutes. The cycle was repeated four times in a day.

DIMENSIONS:

HEADDRESS, 2015

PE sponge

250 x 230 x 230 cm

HANDBAG, 2015

PE sponge, wood

120 x 120 x 80 cm

KEY, 2015

PE sponge, aluminum

280 x 300 x 120 cm

BAG OF FLOUR, 2015

PE sponge, 120 x 210 x 80 cm

PIANO, 2015

PE sponge, textile, aluminum

140 x 120 x 100 cm

PIANO-AND-I, 2017

750 gold, sterling silver

2,5 x 5 x 2 cm (body); 60 cm (chain)

CREDITS:

ENCAPSULATION SUITS (trial video), 2014

DANCERS: Oliver Pollak, Karla Knie, Roberta Del Ben

DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY: Florian Lampersberger

PHOTOGRAPHER: Öncü Egemen Gültekin

VIDEO EDITOR: Maja Tennstedt

LIGHTS: Gil Bartz

TEAM: Jane Saks, Yuri Tetsura, David Adoga, Sabrina Bergamini

ENCAPSULATION SUITS, 2017

ACTOR: Yuka Oyama, Ulrike Kley (eyes from outside)

DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY: Florian Lampersberger

LIGHTS/PHOTOGRAPHY (PERFORMANCE): Gil Bartz

PHOTOGRAPHY (SCULPTURES): Attila Hartwig

EDITOR: Maja Tennstedt

PROJECT MANAGER: Roberta Di Martino

ASSISTANT: Julie Beugin